Approach to Teaching

Early on in my teaching career, I was discussing the concept of audience with my students. This idea of tailoring your work to address a specific audience was intuitive to many students, but when it came to applying the concept–actually writing the words that speak to a specific audience–many struggled. I realized that learning rhetorical concepts were fundamental, but only meaningful if those concepts could be effectively applied. Giving students the space they needed to practice concepts in their own work became a central tenant of my pedagogy. Connecting theory and practice for my students with applied assignments and exercises underpins the goals of my courses and formed my interest in TPC. The applied focus of the service course, and many courses in the undergraduate major or other degree programs, helps students to see how ideas manifest in writing. These courses not only ask students to think through how theoretical concepts can be applied, but that also allow them to practice what they’re learning.

My past teaching experiences helped me realize that what I appreciate most in teaching writing is to show students how the skills and knowledge they are learning can transfer directly into the world of work and into their civic lives. Facilitating my students’ learning in a way that helps them make connections to their own lives is a cornerstone of my own practice. This emphasis on application and moving knowledge across experiences has led me to my pedagogical approach:

- situating learning on a continuum,

- fostering an open learning environment, and

- building knowledge and developing skills.

Situating learning on a continuum

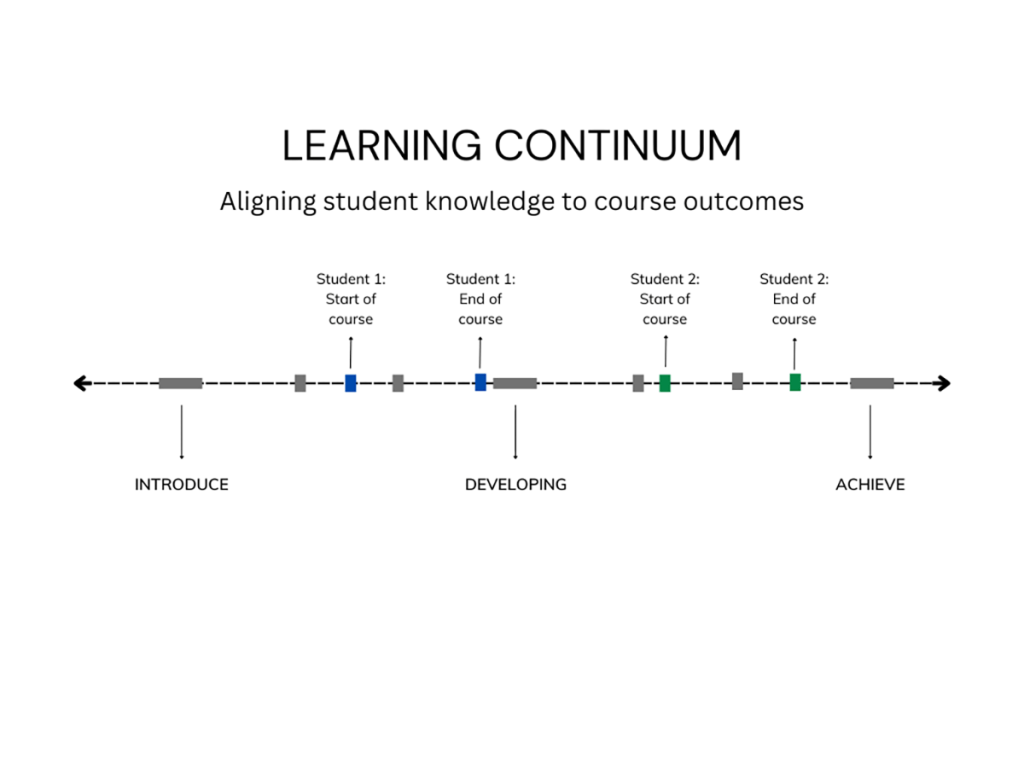

We must be aware of who our students are and the knowledge they enter with. Viewing learning on a continuum, or spectrum, means each student gains knowledge at their own pace and is assessed on their progress within the course. This does not necessarily mean mastery of every concept but meeting the student where they are and understanding that individual mastery of concepts looks different for each student. For example, the ability to write professionally may be the goal, but each student’s style and understanding of what it means to be professional will impact their achievement of this goal. Therefore, each student achieves the goals of the course at a different pace (see fig.1).

Figure 1. Student learning continuum

Student centered pedagogy is more than just knowing students need to get something out of what you’re teaching them. It’s about designing the course (and the materials within it) to be focused on what those students need. It includes being aware and reflective of the way in which you approach talking to them and how you evaluate them. Establishing clear and purposeful goals are a way to do this, specifically, assignment goals that align with course goals, and then explicitly and transparently communicating those goals to students in a language they can understand and value. If students understand why they are doing a task and how it contributes to achieving a goal the work they do is both more meaningful and relevant. Goals, or outcomes, for assignments, courses, and programs can all help uncover the reasoning behind writing courses and forge a clear connection to professional practice. By designing the course and its outcomes in this way, students are able to gain knowledge by connecting course concepts and practices to their own experience. For instance, because I have foregrounded actionable outcomes in teaching assignments, when leaving formative feedback on writing projects, I am able to reference where the outcomes apply in the students’ work. Students receiving this feedback are able to connect comments to their experience in class and how those experiences connected to their own writing. This connection between concepts and their own writing allows them to think critically about where they fall in their own understanding of larger concepts, thereby giving them the chance to improve based on where their knowledge began. Therefore, learning is on a continuum. This approach allows students to not only articulate their knowledge, but to build on their own skills without being held to a standard that they are unable to reach within a semester.

Fostering an open, inclusive environment

Learning also means being open to new ideas and experiences. Students are going to be challenged, it is in the nature of higher education to push against long held ideas—and within professional writing courses it is even more important to be direct and transparent with our students. To do this, I ensure the policies and attitude within my classroom reflect honesty and openness—from the feedback I give to the instructions and explanation in class.

One of the main aspects of my approach to teaching is that my role in the classroom is one of facilitator. While this is often used as a buzzword, I am committed to my role as facilitator in the classroom because, in order to grow in their own learning, students need to have support and encouragement to take new ideas and move forward on their own. My goal is to get students to think on their own and connect the concepts they learn to the world outside our classroom. For instance, when teaching audience, I ask students to write to audiences that they are familiar with (i.e., professors, collaborators, friends) to illustrate that they already know how to tailor for a specific audience (and that this class will help them develop that ability in different contexts). This helps students connect what they’re doing in the project with how they can use it outside the classroom.

Without a direct and transparent approach, students may not know why they are doing what we ask or what they are learning. Additionally, to help ensure the course is taking a direct and transparent approach, I utilize a check-in method to allow students to offer anonymous feedback via a google form about the course progression and clarity of expectations and assignments. Many students greatly appreciate this opportunity, and it offers me a chance to adjust my practice in real time, as a response to their concerns. Taking time to be explicit and uncomplicated, mitigates confusion on the students end while helping to solidify their knowledge and be involved within the community of the classroom. Adjusting practice during the semester, as well as being explicit in expectations, also allows for students to become invested in their own learning. This also helps to diminish students’ impulse to rely on AI.

Building knowledge and developing skills

In order for students to build knowledge, they must be supported by their environment. Expecting students to understand how to critically think, without giving them the opportunity to learn and practice does not help them. Taking larger concepts, breaking them down into manageable pieces and practicing them helps students build on their own knowledge while making connections to other areas of their lives. For instance, assignments are more meaningful if attached to specific contexts. Asking students to “critically think” about how elements of design work on a page will not be useful unless it is paired with problem solving for a specific issue. For example, in a visual communication class, if the focus is on students learning page layout principles, then they need practice analyzing examples as well as designing according to specific needs. Problem solving allows students to see the significance of a principle in situ, enabling students to learn a piece of the skill and build on it throughout the semester.

In my class, I work to form a collaborative community. We engage in a range of instructional strategies, including working through concepts in small groups to explore ideas and generate discussion questions. We then have discussions together, and they ask questions of myself or their peers. When students are working in class, this is a time for them to problem solve. I want students to develop the ability to look for answers on their own or collaborate with their peers to figure it out. We also have time for discussion in which the whole class participates, which builds on the problem solving done and adds in analytical skills as well. To do this, students complete an assignment on their own or with their peers and then we talk through it as a class. For example, in a discussion on visual design, class discussions are prompted with questions such as “what was done well” and “what can be improved,” as opposed to a dynamic of “what is good or bad about this”. Students offer critique and revision suggestions for the design based on the readings and assignments previously done in class. This reflective practice encourages students to see the issues within the document while moving towards how they can make it better. These questions also remain the same, taking the pressure off of students who wouldn’t typically participate, and allowing them the opportunity to mentally prepare and jump into discussions. Not only do these practices encourage students to sharpen their problem solving and communication skills, but they also help to strengthen the community within the class.

Throughout all of my approaches, preparing and supporting students is central. Understanding that in order for students to be successful, we need to acknowledge that students have varying degrees of knowledge and the key to their success is a supportive classroom where they can strengthen their skills. Because of this, it is important for me to meet my students where they are in their knowledge and help them build their own skills in a way that promotes an open and rewarding learning environment.